Written by Retha van der Schyf

It’s not just E, S, and G; it’s how they interconnect

ESG, short for Environmental, Social, and Governance, has gained significant traction as a cornerstone framework for assessing and fostering sustainability. ESG, as noted in previous articles in this series, evaluates the essence of a company’s performance and impact in these three crucial areas. But it is increasingly so much more than that.

What makes ESG truly powerful is the intricate web of interconnections and interrelations between these elements as they collectively frame a company, but increasingly also a town, a society and even a nation’s sustainability profile.

But the question that often arises is whether one of these factors is more significant than the others. Does the E, S, or G have a more substantial influence, and is there an ideal starting point for companies or societies looking to improve their ESG or sustainability performance? In this article we delve into this debate and explore the synergies and dependencies among environmental, social and governance factors within the ESG framework.

Does the E reign supreme

The “E” in ESG represents a company or a society’s commitments to environmental stewardship. It refers to actions taken to reduce carbon emissions, conserve natural resources, protect and enhance biodiversity, and to minimize ecological footprints.

I have had numerous spirited debates with environmentalist who passionately believe our world’s future can only be secured through environmental strategies, and therefore that the E is the most important element. Recognising the current overwhelm of evidence of environmental threat the world over, there is plenty persuasion to their point of view.

They are however less certain when the view is presented that more than half of our current world is living in such challenging socio-economic conditions that they literally – in physical and emotional terms – cannot afford to be concerned about macro environmental threats.

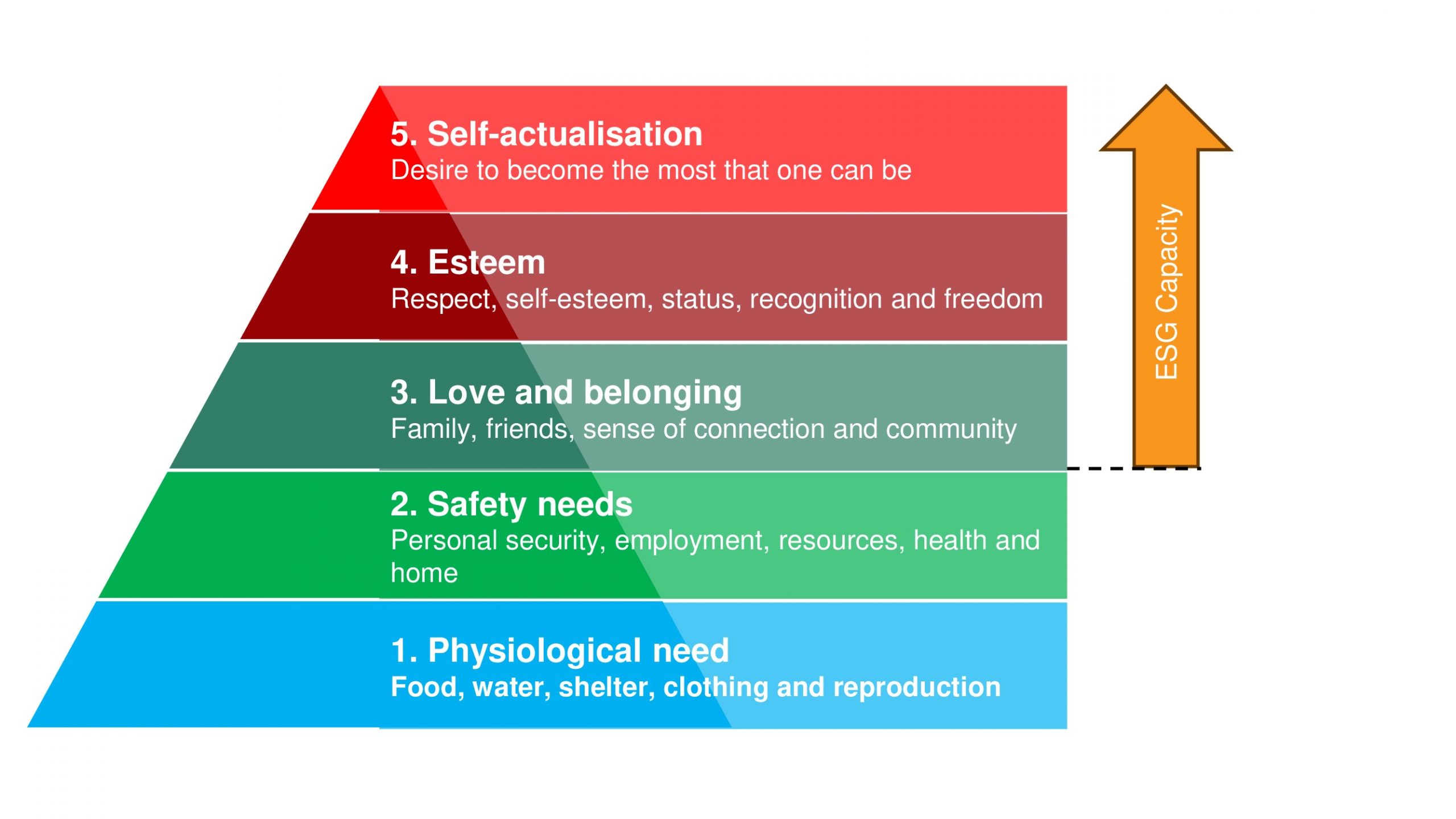

As depicted in figure 1, Maslow’s Hierarchy is a well-known psychological framework that outlines human needs and motivation. It advocates that individuals naturally need to prioritise fulfilling their basic needs, such as physiological needs and safety, before advancing to higher-order needs, such as belonging, respect and personal fulfilment. The by-product hereof is that individuals, groups or communities that are so poor that they have no choice but to be preoccupied with solving for their basic needs, cannot “afford” the luxury of being concerned with carbon footprints and recycling. Their immediate focus on day-to-day economic survival far outweighs a need to focus on securing a long-term future for the world. For a society to have the capacity to focus on environmental concerns, there is a need to address in parallel the socio-economic conditions that imprison some parts of our societies in their predominate focus to merely keep their noses above water.

Another example of the intricate link between the E and the S is to consider the local social attitudes in relation to environmental well-being.Societies conform to mindsets and patterns of behaviour shaped over decades. These eventually form collective cultures, and vice versa. Therefore, if the predominant current social culture and collective mindset is that environmental remediation is the public sector or large companies’ responsibility to resolve, the society and the individuals within it will be oblivious to any personal responsibility they may, could or should have. By example, Scandinavia has a 40-year history of national recycling, whereas in Greece it is still not usual in both urban and rural settings to discard waste in public spaces as “someone else” will take care of it.

In this example, achieving basic standards of environmental impact responsibility on an individual or community level require a conscious shift in the social mindsets and behaviours, and therefore an equal focus on both the E and the S.

Does the S reign supreme

The world over, and southern Africa in particular, is increasing their breadth and depth of focus on the S, the social element in ESG. This element is a broad category that, as discussed in article 6 of this series, includes a wide spectrum of humanitarian and sociological topics, ranging from basic human rights, social justice and inclusion to social wellbeing and societal agency.

Both public and private sector participants that seek social licences, increasingly advocates strongly for prioritised investment in the social element of ESG. In truth, everyone ideally wants to reduce poverty and to see more inclusive, equitable and healthy societies. But the uncomfortable reality is that to solve for social issues more sustainability, we need to address economic value chains to allow for greater access to economic means that far exceeds philanthropy and public sector subsidies.

Simply put, the social issues we are looking to solve for are more often than not symptoms of socio-economic and economic challenges that require a rethink and a redesign. It leads to a strong argument that to solve for key social issues, we need to focus our ESG efforts on extending economic value chains and systems to achieve greater sustainable inclusion, circularity, and socio-economic resilience.

The social element is also not more important that the governance element. If employees, customers or community members do not believe in the good governance of its employer, local companies or in public sector governing bodies, the latter loses credibility and operate with reduced societal support. This in turn causes direct and indirect dilution of collective cohesiveness and stability.

Does Governance reign supreme

The “G” in ESG represents transparent, ethical and inclusive governance, albeit at a company, a society or a national level. Consider a scenario where a company demonstrates impeccable governance but neglects its environmental responsibilities. Despite ethical leadership, a lack of environmental concern can tarnish the company’s reputation and long-term sustainability. Conversely, robust environmental and social initiatives may flounder if the governance structures around it are questionable.

Similarly, in the broader societal context, there are countries, such as China, Russia and Saudi Arabia that have healthy public and private sector governance practices but lack credible performance in environmental conservation or social equality. While efficient governance may ensure strong policy implementation, the absence of environmental sustainability and social inclusivity will lead to public dissatisfaction and discourse in the long-term. Conversely, a nation championing environmental and social causes but grapples with governance issues, may face challenges in policy enforcement and compliance.

In closing

While it may be tempting to rank ESG factors in order of importance, it is essential to recognize that the three factors are interconnected. It is not a question of one being more critical, and neglecting one can weaken the others. It is rather about recognizing the inter-reliance across all the elements, and how they interweave to shape and strengthen a company or a society’s sustainability profile. Instead of singling out one factor out of habit, political correctness or because of local cultural biases, companies, communities and nations should strive for a balance across the trilogy of elements to achieve the desired and required net positive impact on our societies, eco-systems and our world in the long-term.

About the Author

Retha van der Schyf is a socio-economic strategist that works with private sector, CSOS and government organisations to transform economies, societies and conurbations. For more about the author, refer to:https://www.linkedin.com/in/rethavanderschyf/