Seabed mining in Namibia is not a new commercial activity. Although current marine mining activity does not directly overlap spatially with operations of the commercial fishing sector, both industries have co-existed in the same marine ecosystem for over 25 years, allowing for both industries to become major economic contributors.

To ensure their co-existence can continue and their environmental impact is kept to a minimum, both the marine diamond and fishing industries are monitored and managed. The same approach should also be considered for the marine phosphate mining in Namibia, which has a comparatively smaller footprint in the marine ecosystem and will not encroach on any of the commercial activities in the marine space.

What is the perceived threat of marine phosphate mining in Namibia?

Since 2012, fuelled by misinformation, the conflict suggests a scientifically unsubstantiated threat of potential catastrophic and irreversible damage to the marine environment and the collapse of the fishing industry.

However, a considerable volume of site-specific surveys, scientific studies, evidence and expert opinion conclude that future marine phosphate mining, like existing marine mining:

- will also present no significant harm to the Benguela marine environment,

- can coexist without posing any threat to the commercial fishing industry,

- can contribute significant socio-economic benefits that are far greater than the costs to the environment, as is the case with marine diamond mining.

Seabed Mining in Namibia is a Dredging Method used Globally for 30 Years

To illustrate that the co-existence of sectors is possible in Namibia’s marine ecosystem, it is useful to compare how similar marine industries have operated concurrently in other parts of the world.

In Namibia, current and proposed seabed mining operations are based on a dredging process but utilitise different dredging technologies. Seabed mining for diamonds is conducted using remotely operated tracked machines or vertical rotating drills to remove diamond bearing sediments from the seafloor for processing onboard the mining vessel. Onboard the mining vessel, the diamonds are recovered and the majority (>95%) of the dredged sediment is discharged back into the ocean onsite.

The proposed seabed mining for phosphate will be conducted using a modified version of the standard trailing suction hopper dredge to remove phosphate bearing sediments from the seafloor for processing. Most of the dredged sediment (>70%) is retained in the dredge hopper and then transported either to a dedicated marine based facility or an onshore processing facility to produce a phosphate concentrate.

Similarly, the UK marine aggregate mining industry (fleet of 28 dredgers) has been operating for 30 years and is a similar dredging operation to that proposed by the marine phosphate industry in Namibia, only at shallower water depths. The vessels remove the top layer of sediment and transport the material to shore

Globally, there are many current examples (United Kingdom, Belgium, Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, to name a few) where marine commercial industries, including seabed mining/dredging, Oil and Gas, and Fishing, have co-existed effectively for many years based on the application of accepted management principles and structures for co-existence.

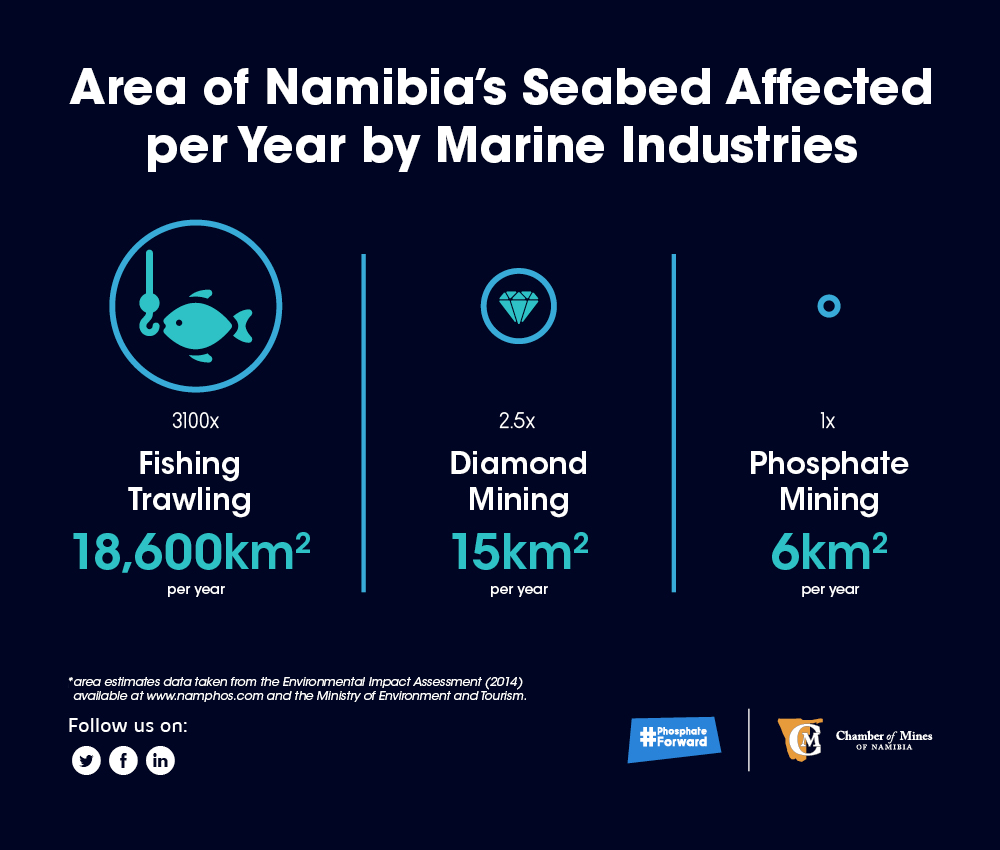

Phosphate Mining’s Impact will be Significantly Less Than Namibia’s Current Marine Activities

Using similar dredging processes, seabed and environmental impacts of both marine diamond mining and phosphate mining operations are similar. However, the scale of impacts differ due to the sizes of the mining areas on the seabed.

Current marine mining impacts a larger area and affects greater expanses of the ocean floor ecosystems than the envisioned phosphate mining activities. Commercial demersal fishing operations (bottom trawling) also impact the seabed and marine ecosystem but are undertaken at a far larger scale than both the current and proposed seabed mining operations.

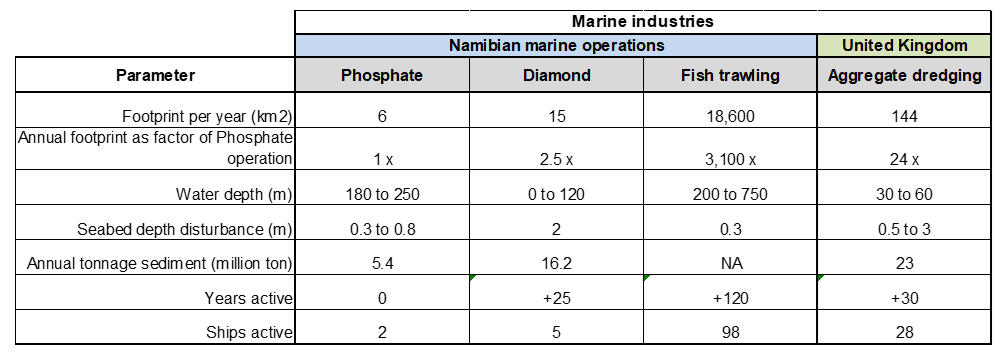

The table below provides a comprehensive comparison with all Namibian marine industries as well as the UK dredging industry, as mentioned earlier.

From this table, it is interesting to note that:

- the footprint of marine diamond mining is 2.5 times that of marine phosphate mining,

- the footprint of fish trawling is a massive 3100 times that of marine phosphate mining,

- the UK dredging industry has a footprint 24 times that of marine phosphate mining,

- volumes of sediment removed by diamond mining is 3 times that of marine phosphate mining,

- volumes of sediment removed by UK dredging industry is 4.3 times that of marine phosphate mining,

- operational water depths of marine phosphate mining hardly overlaps with fishing,

Does Namibia’s Seabed Recover from Seabed Mining?

Abundant conclusive physical evidence and an extensive body of scientific data on the recovery of the seabed has been gathered over the past 20 years, and the two main findings of the 2008 BCLME Report[1] on the Cumulative Impacts of Seabed Mining (over a 10-year period) are that:

The impacts of seabed excavation for marine diamond mining do alter the habitat in the mining area,

but are not significant at the scale of the operations when compared to the overall marine ecosystem and,

The seabed does recover over time, albeit at differing rates

[1] The evidence is held in various reports and studies commissioned by and held by the Benguela Current Commission, Namdeb and various government ministries, which includes a report relating to the Assessment of Cumulative effects of marine Diamond Mining Activities on the BCLME Region prepared by Pisces Environmental Services (Pty) Ltd for the Benguela Current Large Marine Ecosystem (BCLME) Programme (March 2008). The report is available on www.benguelacc.org

Key to Successful Seabed Mining: Monitoring, Management, and Legislation

In the UK, the environmental effects of the marine aggregate mining industry (a fleet of 28 dredgers) have been carefully monitored for 30 years under a stringent regulatory framework, which has been supplemented over the years by industry-led initiatives through British and European Dredging Associations. The UK aggregate mining industry work in collaboration with the fishing, oil & gas, renewable offshores, pipeline and cable, archaeological, recreation, and tourism industries to carefully monitor the impact of dredging operations. The examples of mutual coexistence and data from monitoring efforts support the inclusion of a marine phosphate industry in Namibia, alongside existing marine mining industries and fishing.

In Namibia, given the small size and scale of the proposed mining activities, a comforting element is that adequate controls and measures already exist in current legislation to regulate marine phosphate mining activities, alongside existing commercial marine activities (Minerals Act 1992, Environmental Act 2009).

A Mutual Co-Existence of Marine Industries is Possible

The combined annual footprint of the envisioned phosphate mining projects is significantly smaller than marine diamond mining and fish trawling. Marine mining and commercial fishing have operated in the same marine ecosystem for the last 25 years, with adequate mechanisms in place to monitor, control, and evaluate their impact on the marine environment.

The scientific evidence available, and a comparison of other areas employing similar mining methods, confirm that a mutual and harmonious co-existence of sectors is possible and the inclusion of marine phosphate mining into the marine ecosystem will neither be detrimental to Namibia’s fishing sector nor her environment.