Written by Retha van der Schyf

Connecting the Dots

The Social element of ESG is notoriously challenging to wrap one’s head around and is perceived to be more complex to solve for than the Environmental and Governance elements. This is partly because the definition of the S is still far less clear than the definitions of E and G. It also has much to do with the fact that the S points wholesale to us as humans – our social constructs, our human conditions and our human conditioning. It is by nature more qualitative and emotive, making it harder for us to be objective about. This leads us to shy away from what is fast becoming the new epicentre of ESG.

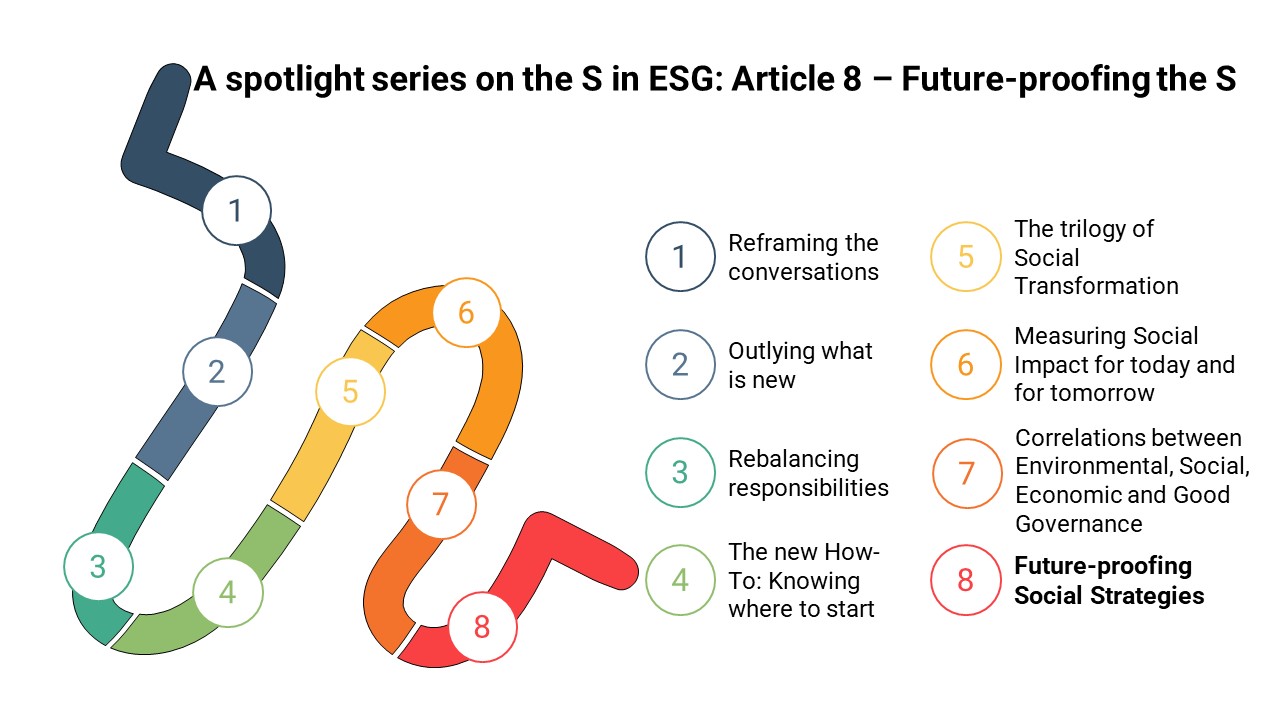

The purpose of this eight-part series of articles on “The evolution of the S in ESG” has been to shed some light onto the aforementioned.

To have the right departure-point on ESG’s purpose, we first set out to explore what changed in our world context that led to the very need for an ESG framework. We continued to explore the notion that ESG is potentially merely another checkbox that organisations need to comply with. Instead, we built a case that ESG is in fact a guiding framework aimed at directing organisations towards better individual and collective behaviour, in relation to categories described by the E, the S and the G. In other words, we instead proposed that by focusing on ESG’s underlying intentionality, we have a moonshot towards greater sustainability.

From there we focused more strongly on the S, pointing out the need to reframe questions in relation to social sustainability, including the recalibration of responsibility for it across the public and private sector, as well as civil society. We proceeded to highlight some how-to and impact measuring considerations despite its qualitative nature, and in article 6 we ultimately challenged the currently unhelpful narrow formal definitions of the S to also include progressive definitions such as social conditioning, wellbeing and resilience. Our penultimate article focused on the unique opportunities at the intersect between the S with the E and the G.

In this final article we, at Salients, highlight the emerging trends we foresee on the horizon concerning the S.

Into the Future

The world currently has a predominant focus on environmental sustainability. This is for patently obvious reasons.

We here, however, want to suggest that human constructs and systems – i.e. social, including anthropology and social psychology, as well as economic constructs have strong direct or indirect bearing on environmental sustainability and governance risks. The S should therefore no longer be in our blind-spot in terms of focus. Many solutions that can exponentially redirect environmental and governance risks in big and small ways, lie in the domain of the S.

Observing recent boardroom discussions, Salients is no longer alone in this thinking.

In light hereof, our prediction of soon-to-be emerging trends in relation to the S include:

a. Much broader definitionBy definition and in practice, the S currently focuses on an organisation’s impact on people and society through lenses of labor practices, community relations, diversity, and human rights. Simply put, it has a primary focus on social justice and social rights. In article 6 we pointed to the importance of these focus areas. We however continued to underline that they are not enough to address human constructs and conditioning that no longer work for our new world context, nor allow us to respond to the immediacy for more sustainable outcomes through social re-engineering.

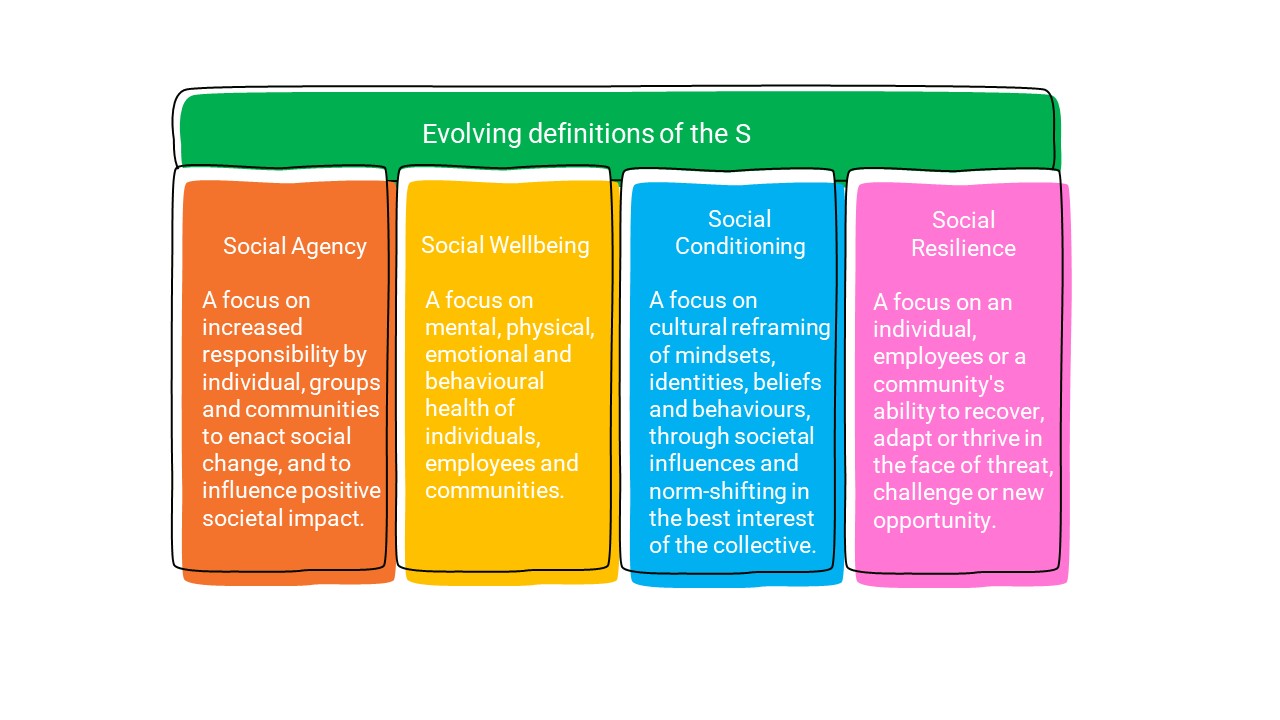

We made a case that the S should fast expand to formally include new concepts such as social agency, social well-being, social conditioning and social resilience.

Figure 1 below describes these factors.

Similar to how we ultimately came to appreciate how the use of coal erodes environmental sustainably, and as a consequence turned towards renewable energy solutions, we now need to become much more critical of social constructs that undermine sustainability, and need to turn our urgent attention to social innovations.

The above new categories help to pin-point which of our social constructs require investment to better complement our new world context. The latter includes the need to address macro threats such as hosting 9.2bn people by 2050, the imminent impacts of population implosions, threats of pandemics and very real risks of flashpoints over scarce resources.

It is easy to disassociate from these macro challenges, but more localised issues over which we can exercise influence, present real opportunity for innovation well within our reach. Simply put, the impetus for investment in boarder S categories is no longer solely for reasons of social justice, but to pre-empt and redirect longer-term local systemic threats to our overall resilience.

In future the S will undoubtedly expand its scope to include socio-economics and neuro-economics with an intent to find solutions in the dynamic interplay between social behaviours and economic systems, blending insights from sociology, neuroscience and economics to understand how their interplay impacts global and local sustainability. This will in turn directly influence how societies behave in terms of the E and the G to foster more appropriate long-term value creation for businesses, economies and societies.

In practice, businesses are already increasingly expected to contribute to the communities in which they operate. This is evolving far beyond traditional philanthropy to include active engagement in local community development, education, and healthcare initiatives. Kelp Blue’s Blue Schools in Lüderitz is one fantastic example of organisations beginning to, independently or in partnership with local governments, non-profits and other stakeholders, address social challenges that will ultimately result in more resilient communities. This trend aligns with the growing emphasis on creating shared value, where business success is directly linked to societal progress.

Finally, Salients has long been advocating for the need to expand the ESG framework’s scope to overtly include another “big” E that expressly speaks to examining Economic constructs that will help achieve greater sustainability. This new element should overtly include focus on local beneficiation and capacity building, maximizing economic access across value chains and driving expanded economic impact through modern enablement rather than through philanthropy. The new “big” E should further include formal requirements in relation to achieving economic circularity.

c. Pooling of resourcesAnother emerging theme across boardroom discussions that echo our thinking, is that individualised efforts towards social reengineering is not enough. Organisations are beginning to realise that to make real dents into societal issues that threaten sustainability, organisations increasingly need to pool their resources, whether at industry, supply chain or shared community interest level. This evolution will transform biases and principles that thus far have led to individualised and even competitive approaches to social investment and philanthropy. Pooling of resources will yield much greater return on investment, even if it is with unlikely partners compared to the ordinary course of business. d. Solving at scale

Solving at greater scale for the “S” is another growing trend as leaders and organisations increasingly recognize the importance of addressing social issues systemically. Large-scale and wholesale solutions will amplify impact, foster inclusive growth, achieve return on investment and will meet rising stakeholder expectations for social responsibility that enhance societal well-being. An “order of magnitude” approach leverages economies of scale, builds cohesion, and leads to exponential innovation that can tackle complex social challenges more effectively. e. Introducing new measures

In article 5 we explored how the qualitative nature and indirect correlations of the S make it harder to measure or to express impact. Our biases lead us to overfocus on what we can count or point to.

What will overcome this hurdle is the use of composite measures. Composite or multiplex measures combine several factors to present a single measure or index that we can relate to and use to compare apples with apples.

A familiar example is the United Nations’ Human Development Index. It combines average achievements in health, education and income to present a single, but comparable index of the states of human development at country level.

Several more of these composite measures will soon emerge to help qualify a country, and increasingly a community’s level of social wellbeing, socio-economic state or social resilience.

This trend represents a major opportunity for clarity, targeted investment and thereby increased impact.

f. Employing technology and big data

The digital divide has become a key issue, with access to technology and digital skills being essential for economic participation and for our purposes, social inclusion. Organisations are increasingly playing a pivotal role in bridging this divide by investing in digital infrastructure and advocating for digital inclusion policies. This trend reflects the growing recognition that digital equity is crucial for fostering social and economic development, especially in underserved communities.

In parallel, the use of big data is another major trend that will enable more precise analysis of social issues that threaten global and local resilience. It will help to identify the impact of hidden social patterns more easily, and to drive data-driven decisions. It will play a major role in enhancing social responsibility initiatives, optimizing resource allocation, and improving stakeholder engagement.

The net result is that it will empower organizations to tackle social challenges more effectively and transparently, and with more precision.

A practical example is the use of big data to determine which social investments will result in the biggest increase in social well-being or resilience in a community. In the absence of a more scientific approach, we are currently at risk of directing efforts towards issues that serve commercial, political, individual or minority biases rather than towards areas where there is more objective opportunity for maximum return on investment.

The last word

In conclusion, greater global and local sustainability serves as both our imperative and our motivation. We are on the one hand forced there by threat, and on the other hand inspired there by deepening appreciation of our world’s interconnectivity and fragility. In this quest, ESG is merely an initial framework that guides us towards this broader aim. The framework will and should evolve. It may even be replaced. It is therefore in our interest to instead focus on ESG’s underlying intent.

In this series we took a close look at the intent behind the S in ESG and concluded that although we have made enormous strides in social investing, we may still be overinvesting in symptoms, and underinvesting in root causes.

World focus is fast evolving far beyond the realms of philanthropy and social justice. A more comprehensive approach will ensure that social considerations are not just add-ons but are essential elements that contribute wholesale to the overall stability and sustainability of our societies.

Ultimately, the true measure of success will be our ability to create resilient, inclusive, and sustainable outcomes for future generations. Time will tell if we are doing enough fast enough. I am quietly hopeful.

About the Author

Retha van der Schyf is a socio-economic strategist that works with private sector, CSOS and government organisations to transform economies, societies and conurbations. For more about the author, refer to:https://www.linkedin.com/in/rethavanderschyf/