Written by Retha van der Schyf

It is commonly agreed amongst Namibian Impact Investors and ESG experts that Namibia, and Southern Africa as whole, will materially benefit from an increased focus on social impact, the S in ESG. This ambition is not set to the detriment of the E or the G. The intent is rather to meet the high standards already set for these, especially for environmental sustainability. The ultimate drawcard is to accelerate the social dexterity and resilience of Namibia in its own interest. An added cherry on the cake would be to unlock the multiplier effect that can stem from optimal interactions across these three pillars of sustainability represented by the ESG framework.

What prevents us from leaning into this opportune evolution of social impact development is complex. Social impact largely deals with humanity – our conditions, conditioning, histories, identities, behaviours and psychologies. It is therefore multiplex. Overlay that with Southern Africa’s geo-political history, it becomes even more thorny to engage with and is fraught with uncomfortable dilemmas that naturally result in unconscious avoidance. More murkiness is added by the fact that we largely still operate in siloes rather than smart collectives or partnerships when it comes to solving systemic social challenges – locally or more broadly. The final fulcrum is the qualitative nature of social impact, making it challenging to describe, measure and quantify.

It is this final aspect of social impact measurability that this article in the series of the evolution of the S in ESG will focus on. Starting with the fundamentals, we will first remind ourselves why we measure social impact in the first place. We will then look at some general and unique attributes of how to measure social impact, before briefly standing still on what we aim to measure despite the challenges referred to. This will hopefully shine a light on the evolving scope, nature and definition of social impact to help further unlock Namibia’s incredible innovation and impact potential in this regard.

Why measure social impact

As noted before, ESG is a framework that engenders a common language on nuanced concepts that describe Environmental, Social and Governance impact criteria. As a result of this characteristic, it has become possible to use ESG as a mainstream reporting framework by which companies’ contributions on Environmental, Social and Governance impact can be comparatively expressed and measured. ESG impacts are on the one hand measured for important external-facing purposes such as corporate branding, investor attraction, and legal or corporate compliance commitments. These are very important motivations, but prioritising these drivers may risk ESG becoming a tick-box exercise.

On the other hand, inward-facing reasons for measuring ESG impact are arguably more directional in value-creation as it informs important internal investment capacity decision-making. In this case impact is measured to answer inspiring questions such as:

- Where is our effort exponentially best spent, and therefore what areas of impact best align with our vision, purpose and capacities?

- Is the effort we are applying having the intended impact, and therefore is the right approach being applied to the right challenges for the right reasons?

- Is our effort having the size and scale of impact intended, and therefore are adjustments to our approach required?

- Is our intended impact materialising within expected timeframes, and therefore are adjustments to our approach required?

- Are our risks being effectively mitigated, and therefore are adjustments to the approach required?

Neither the externally nor the internally focused reasons for measuring social impact is more important. The insight is rather that both reasons for measuring impact are important. That said, laser focus, creativity, innovation, effectiveness and scale of impact will more likely stem from thoughtfully considered inward-looking measures of impact.

How to measure social impact

Social impact measuring is both a science and an art. Measuring social impact straddles two broad categories of impact measuring: quantitative and qualitative measuring.

In layman’s terms, quantitative measures, which, as an engineering nation we are more comfortable with, refer to what we can concretely measure and count. It has a numerical and statistical nature. For purposes of simplicity, quantitative measures relevant to social impact include social inclusion, education, labour, health and socio-economic access indicators.

Qualitative measures on the other hand focus on the context, textures and nuances of experiences, mindsets, cultures, norms, social patterns and behaviours. It is often interpretative, subjective and relative. This qualitative nature of social and socio-economic impact categories makes it more challenging to measure. For purposes of simplicity, quantitative measures relevant to social impact may include agency, empowerment, conditioning, identity, norms, collaborations, well-being and social resilience indicators

Qualitative measuring uses tools that draw on social indices and surveys, narrative based evidence, community participation and co-creation practices, composite indices and comparative or relative data expressions. These measuring tools require active involvement and bilateral engagement by the recipient communities. It is paramount for those wanting to contribute to social impact development to become comfortable with qualitative measuring of impact.

Besides the skills to employ both qualitative or quantitative measures to express social impact, the fundamentals of collecting baseline data, and taking an informed snapshot of a current state, remain important. These comparative starting points, which are never too late to capture, should thereafter be complemented by periodic assessments of the actual impact of the intended social investment. This by implication means that a skilled person or team should be tasked to account for regular impact assessments.

A further differentiating consideration in measuring social impact is the likely timescales of impact. Because of its human nature, time-horizons of the return on investment of social impact strategies might take much longer than first assumed. This means social impact investment expectations should include micro, macro and mega impact cycles. Mega cycles refer to 10-year time horizons or more. For organisations use to short feedback loops and reporting cycles, this may require seismic adjustments to their investment expectations, mindsets and strategies.

Finally, in part because of the small size of its population and economy, Namibia has not yet needed to develop an advanced culture of data collection and interpretation, albeit qualitative or quantitative in nature. With the trending data evolution word-wide, I foresee an enormous opportunity for Namibia in adopting new data strategies and tools that will underpin a variety of important commercial and economic strategies, but also social impact measuring strategies.

What social impacts to measure

It goes without saying that measures are only valuable if they are employed in relation to meaningful content. This is especially true in the case of social impact measures.

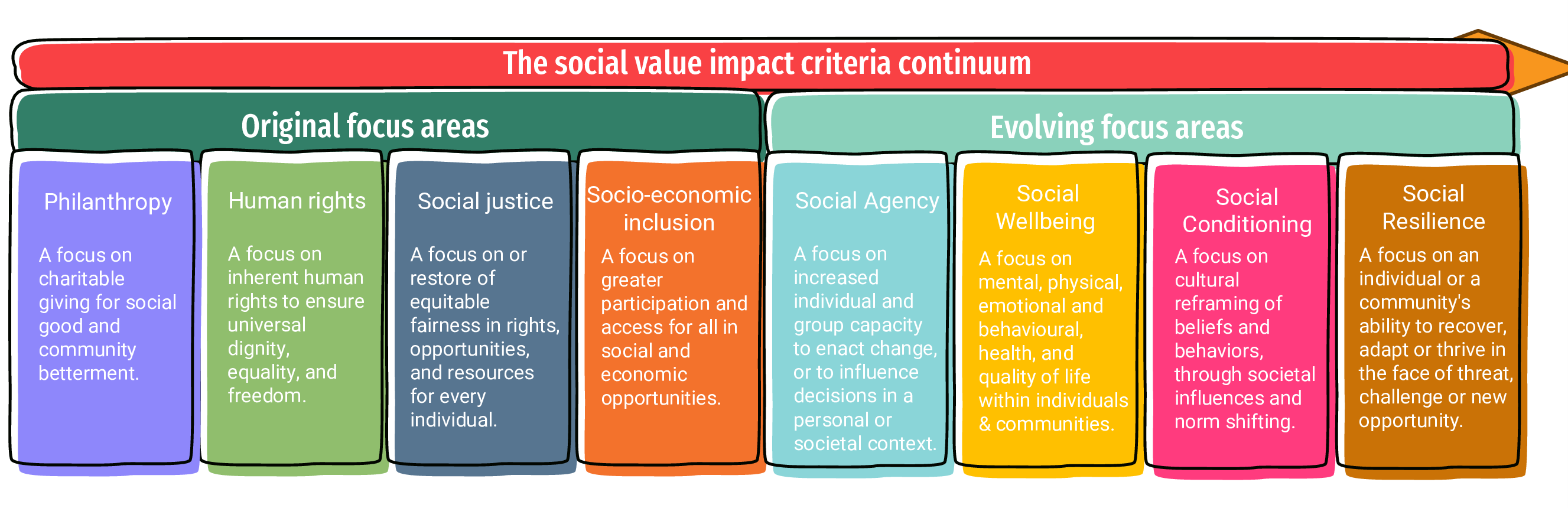

As noted in previous articles in this series, ESG as a framework is not static. This is especially true for the criteria that defines its composite parts. Focusing on the S herein, there has been an explosive evolution in the breadth and depth of appraising social impact categories. Until about 10 years ago, social investment was largely and rightfully focused on philanthropy, human rights and social justice pursuits. These remain paramount to social development. However, with an increase in world knowledge and social consciousness, a variety of new exiting categories are being added, opening doors to new opportunities of systemic social value creation. These new categories have deepened our understanding of social patterns. This in turn has expanded our ability to measure the value being added to small or big social systems for the benefit of participants within the applicable system. The potential this can unlock for greater social wellbeing and resilience for societies, is thrilling.

The table below outlines a growing continuum of social impact criteria that forms part of the S in ESG.

In closing

Measuring social impact for the right reasons and in the right way has the potential to transcend the component metrics it draws on. As Namibia’s strides in sustainable development gain pace, a nuanced understanding of its social and socio-economic dynamics is crucial. Combining quantitative measures with qualitative insights from current social dynamics, socio-economic states, conditioning, norms, mindsets and culture can foster a comprehensive evaluation of initiatives that will unlock a new season in Namibia’s social well-being. This will require a new generation of reframing, renegotiation, collaboration, trust and celebration – an exciting tipping point for Namibia that is within arm’s reach.

About the Author

Retha van der Schyf is a socio-economic strategist that works with private sector, CSOS and government organisations to transform economies, societies and conurbations. For more about the author, refer to:https://www.linkedin.com/in/rethavanderschyf/