Written by Retha van der Schyf

New Mindsets

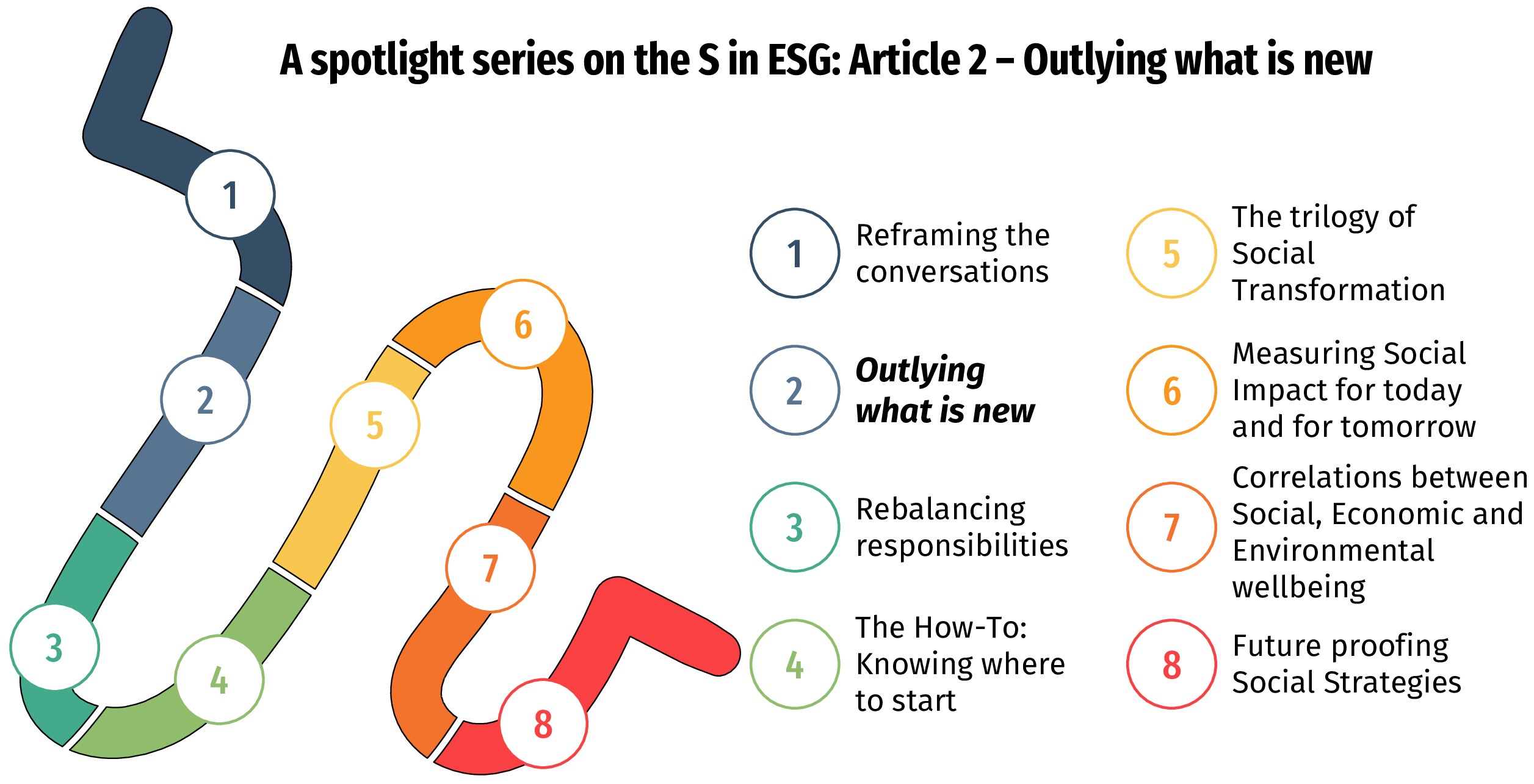

In the first article of the series – ESG: Focusing on the S – we pointed to the value of reframing the thinking and thereby the questions being asked about the S in ESG. The objective is to untie ourselves from past assumptions, expectations, and dialogues to instead direct our full consciousness towards the expansive new horizons introduced with the advent of modern sustainability insights and ESG framing.

With unbiased mindsets we can more clearly spot the evolutionary opportunities for meaningful social impact – in the interest of both businesses and society in general – without necessarily assuming undue responsibilities or putting our hands deeper into our pockets.

New Horizons

In General

At the core, the shift in focus of social strategies today stems from much greater world knowledge and awareness of the interconnectedness of eco-systems. On the one hand, we are all much more informed of the collective threats to local, national and even global fragility and wellbeing. This has focused the urgency for collective solutions. On the other hand, we now also have a much richer understanding of systemic social impacts and their interconnectedness with environmental and especially economic sustainability. And as we all know, knowledge is power.

Specifically

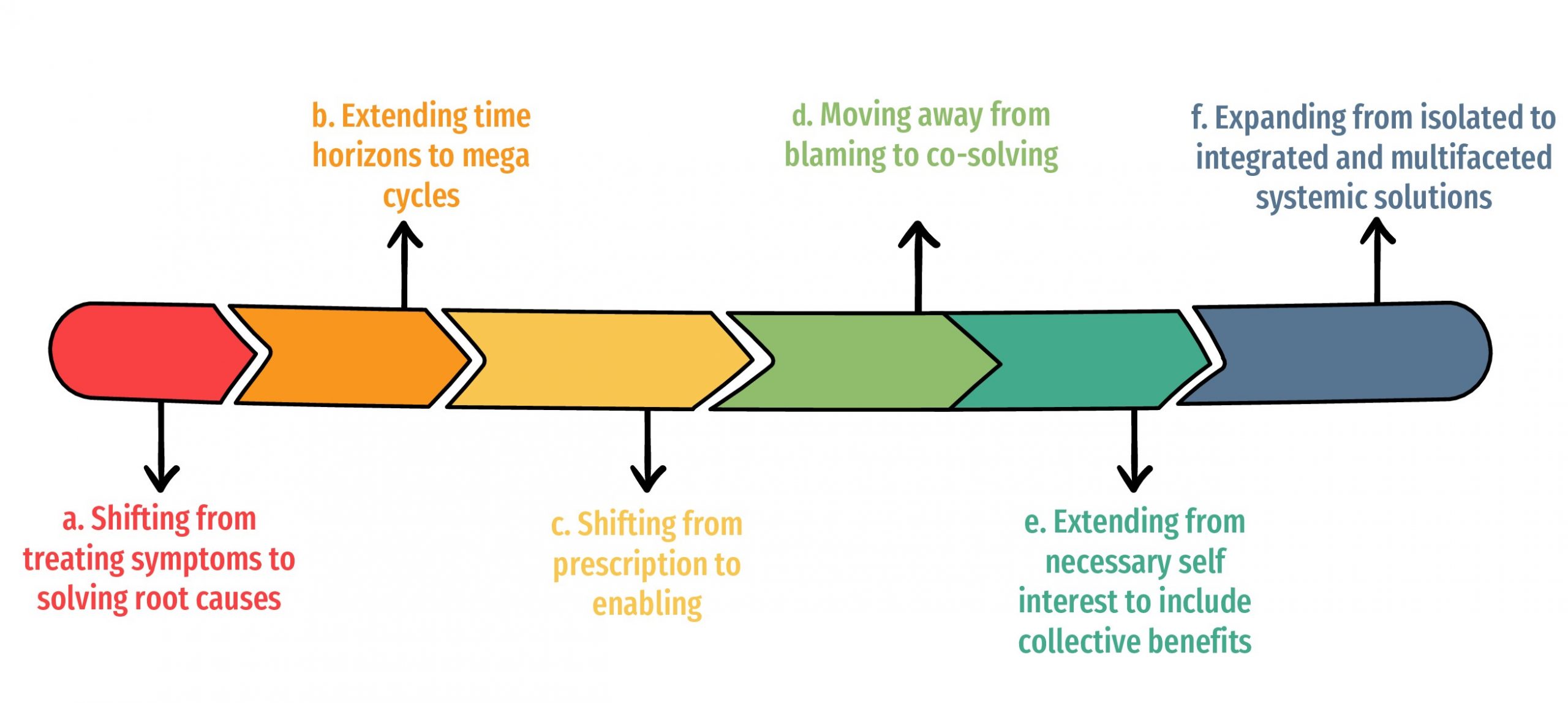

These new world insights have led to 6 important overlapping characteristics that distinguish modern social strategies:

a. Solving the Root Cause

With the benefit of hindsight, traditional social strategies generally focused on solving tangible symptoms of defined social phenomena.For example, a high propensity of alcoholism led to social efforts focused on resulting domestic violence, alcohol prohibitions or curative measures against alcoholism. These efforts are not without merit. New social impact thinking goes further. It also focuses on what causes individual or cultural alcoholic behaviour in the first place, targeting the often intangible root causes of addictive and self-destructive behaviours.

b. Prioritising Mega-cycles

Ambitious social strategies today prioritise the very far horizons, considering transformative impacts up to 50 years into the future, and increasingly beyond the life expectancy of one leader, business, or eco-system. History has taught us that social imbalances take time to course-correct and require visionary action early. Today’s rate of change simply outpaces traditional 2–10-year social transformation goals.

c. Empowering Through Enabling

Arguably the most crucial shift in modern social strategies is that emphasis is finally being placed on equipping and enabling people, communities, and societies, rather than fixing or prescribing social solutions, traditionally from a point of authority. Enabling refers to empowering people with information, tools and skills to help themselves. Instead of prescribing what to do, it equips people and societies to make healthier choices to improve their own wellbeing. A basic example in mining is to inform communities of the value and responsibilities of homeownership instead of providing free accommodation, and to enable them with the choice and means by which to become property owners in ways that do not increase undue risk-taking for anyone.

d. Sharing Accountability

Clear accountability for social transformations has often been a bone of contention. There has been an unconscious tug of war between the Public and Private Sector, leading to misplaced expectations regarding who is responsible for what, to what end and with what means. Modern strategies appreciate that meaningful social transformations rely not only on healthy collaborations between the Public Sector and Private Sector, but also increasingly require active ownership by Civil Society. Few significant social transformations can be achieved by just one constituency. So much more is achieved when these groups interact and collaborate effectively.

e. Increasing Altruism

The most inspiring new social strategies focus on solving social issues that simultaneously have a local and a more widespread impact beyond the periphery of the local ecosystem. For example, in the case of mining this altruistic characteristic increasingly includes solving for social issues that include benefits not only for the mine, but also for the local town or region, whilst simultaneously solving for national concerns such as housing shortages, employment creation and new economic development and access. The innovation lies in using the same investment effort to create more for more.

f. Thinking Systemically

New knowledge and insights have increased our understanding of the fragile interconnectedness of geo-political, economic, business, social and environmental systems. With this understanding, social transformation agendas now prioritise focus areas that will undoubtedly improve social outcomes, but will also have a correlated net positive impact on environmental sustainability, as well as economic participation and performance.

In Closing

The mining industry, and extractive industries in general, have unquestionably been at the forefront of social impact investment in the past.

New technical innovations and economic growth frontiers within these sectors, now overlayed with the global drive for sustainability and resilience thinking, create the perfect platform to reclaim their brand of leading-edge social impact.

The ultimate prize is systemic value-creation, sustainable transformations and holistic resilience development, key and necessary measures of success of the future way of doing business.

About the Author

Retha van der Schyf is a socio-economic strategist that works with private sector, CSOS and government organisations to transform economies, societies and conurbations. For more about the author, refer to:https://www.linkedin.com/in/rethavanderschyf/